This is the fourth blog post responding to the recent post by my friend Aaron Shryock called What is Accuracy in Bible Translation? Here are links to those posts with some important takeaways:

- On Meaning: words have a range of meaning, which can only be understood within context. When translating between languages, words can have overlapping meaning, but a different range of meaning.

- On Audience: even within the same language, words can mean completely different things based on the audience. To know what you are communicating when you translate, you must know your audience.

- On Explication: because the audience of a Bible translation is vastly different than the original audience, it is necessary to explicate some implicit meaning for the new audience to understand the meaning correctly. Explication should be used whenever necessary and helpful. Also, we should only explicate what we know to be true, and to be known by the original audience.

This leads me to my definition of accuracy: A translation is accurate when the original message is communicated to a new audience. No meaning should be added, removed, or changed in the translation.

If I understood his position well, I think Aaron would identify my definition with communicative accuracy, something that he believes is more akin to clarity. On the website I just linked to, you will find a distinction between exegetical accuracy and communicative accuracy. I believe this distinction is unhelpful and confusing. That site defines exegetical accuracy as “how closely a translated text preserves the meaning of the original text.” Communicative accuracy is defined as “the degree to which the original meaning in a source text is understood by the users of a translation.”

According to these definitions, a translation could be “exegetically accurate” but the meaning of the original is not communicated to the users of the translation. How can that be? How could a translation be accurate but the meaning is not understood by the audience? It could be that we have used words that the people in our target audience do not know, or misunderstand. But is that good translation?

This idea of exegetical-but-not-communicative accuracy strikes me as being a bit like the older members of our translation team. These older men tend to have a wider vocabulary than the average Kwakum person. Sometimes they know words that no one else has ever heard of. Other times their understanding of a word is not the common understanding. For example, early on we as a team had to choose a word to represent “sin.” These older translators demanded that we use the Kwakum word sɛmbu, whereas the younger members of the team suggested nsɛm. The second word, nsɛm is a borrowed word from a different language. The older Kwakum people would prefer we never borrow words.

I think that the first time this came up in translation was in the story of Cain and Abel. God says in that story to Cain, “If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is crouching at the door.” (Genesis 4:7). In testing this story, we used the word sɛmbu and asked people what it meant. 9/10 Kwakum people said the word meant “incest” or something similar. So, in this passage they were hearing, “And if you do not do well, incest is crouching at the door.” Is that accurate? Our older translators demanded that it was accurate. At the time, our dictionary said that sɛmbu meant “sin.” So, what should we do?

We tested the word nsɛm as well, and found that 10/10 people understood it as a broad term for sin, offering examples such as: theft, lying, disobeying parents, etc. So, which of those two words is more accurate? Nsɛm is of course more accurate. How do we know? By asking the people what they understood. Remember this illustration from my post On Meaning?

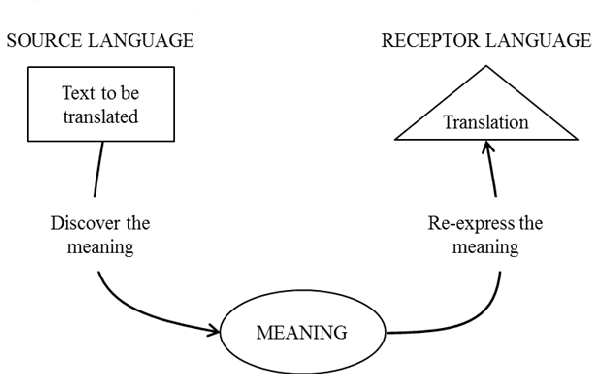

The general process of translation is to discover the meaning of a text (exegesis) and then re-express the same meaning (translation). If I had to distinguish between “exegetical accuracy” and “communicative accuracy,” I would consider the former to refer to the process of exegesis. I am accurate at that stage if I have rightly understood the passage. Then “communicative accuracy” would mean that we communicated the same message without adding, removing, or changing meaning.

In the example of my translators, we understood the word “sin” to be a general term for what we can think, say, or do that is not pleasing to God. I believe that is the exegetically accurate understanding of the word “sin” in Genesis 4:7. However, when we translated it sɛmbu our translation was inaccurate, not because we as a translation team did not understand the word, but because our audience did not understand it. The accuracy is not determined by the translators, or even the dictionary, but by what the target audience understands. On more than one occasion, our testing has led to updates to the dictionary, but it doesn’t really work the other way.

Explication and Inaccuracy

From reading Aaron’s post, it seems like a lot of his argument about accuracy comes from explication (You might want to back to my post On Explication first.) Aaron claims in his post that when we translate, “as little implicit information should be included as possible.” And that, “Accuracy entails preserving the explicit meaning of the source text and not implicit information.” This leads me to believe that Aaron believes that a verse with explication is less accurate than a verse without explication.

I could not disagree more. As per my examples in my previous post, is the “city of Jerusalem” less accurate than “Jerusalem”? Is “sycamore tree” less accurate than “sycamore”? I think certainly not. Rather, for an audience that does not know what Jerusalem is, adding “the city of” is making the text more accurate. Adding “tree” also makes the translation more accurate. Remember, we are not translating words, we are translating meaning. So, when we check for accuracy, we don’t count words. Rather we ask: did we add, remove, or change the meaning of the original?

Of course, explication can add inaccuracy, which is why I said that we should only explicate what is clearly true and clearly known by the original audience. Also, it is unhelpful to explicate everything, as in my example with all the details of the sycamore tree. This information can be included in dictionaries, glossaries, and other resources.

Meaning is Determined by Context on Both Sides of Translation

So again, we do not translate words, we translate meaning. I believe that Aaron would agree that the meaning of a passage can only be discovered in its context. “Context” includes: the text around the passage, the author’s culture, the time period in which it was written, and the audience to which the author was writing. This is why exegesis is so important in Bible translation. One very tricky word we have encountered in the Bible has been the word “world.” In the English Bible the single word “world” has a semantic range that includes: the Earth (2 Samuel 22:16), all people (Psalm 9:8), and even “sinful temptations and desires” (1 John 2:15-17). So, to understand and translate these passages accurately, we must understand each individual context.

Where I think that Aaron and I disagree is that I believe the meaning of the translated text also depends on context. In reality, we don’t translate into a “language.” Like I mentioned in previous posts, there is no “standard Kwakum.” And to the chagrin of my English teachers, there is no “standard English” either. Language is fluid, always changing, and depends on the audience.

Different audiences will interpret words, sentences, and paragraphs differently. The meaning is not in the words by themselves, but in what people understand the words to mean. This doesn’t mean that words have no meaning, or can mean anything. Rather, words have a range of meaning. That range of meaning is then limited by the intention of the speaker, the context of the utterance, and the comprehension of the audience.

Another way to look at it is, when we exegete the Bible we are not seeking the meaning of words or sentences. Instead, we are seeking the meaning of the author. A single word, sentence, or even paragraph can mean many things depending on who is saying them, when they are saying them, to whom they are saying them, etc. The same is true on the other side of translation.

If I said, “Well, I am going to quit my job. After all, Jesus said, ‘Relax, eat, drink, and be merry.'” Is that a true statement? I hope that you wouldn’t simply say, “No,” because Jesus did say that (see Luke 12:19). But I hope you would not just say “Yes” either. Jesus did say these words, but did he mean for me to quit my job? No. That was not his intent. How do I know? Context. Jesus put these words in the mouth of a rich man in a parable and then called that rich man a fool.

When we translate we have to seek the meaning of the author. We do this by studying the passage, the book, the Bible, the geography, the language, the culture, etc. When we understand the meaning of the author as best as we can, we then study the new audience (the Kwakum): their language, culture, understanding of the Bible. Then we seek to communicate that original meaning to a new audience. That is translation. In order to translate accurately I have to know both the original meaning in its context, and the meaning that is communicated by the translation in a new context. That translation is only accurate when it communicates the same meaning as the original to the new audience.

Aaron used a quote in his post from the experienced translator, Eugene Nida:

Actually, one cannot speak of “accuracy” apart from comprehension by the receptor, for there is no way of treating accuracy except in terms of the extent to which the message gets across (or should presumably get across) to the intended receptor. “Accuracy” is meaningless, if treated in isolation from actual decoding by individuals for which the message is intended.

I don’t agree with Nida on everything he has written, but this quote is spot-on. To think of accuracy as something apart from comprehension is to act like language is something that exists apart from people. Language only has meaning in that it communicates to an audience. Since culture and audience change over time, we have to update Bible translations. Did you know there are American and British versions of the ESV? Both are accurate when in the hands of their intended audience. But the British version is not necessarily accurate in the hands of an American.

Quick aside: I am not talking about meaning like post-modern English professors do. When testing, we do not read a passage and say, “What does this passage mean to you?” That is a good question to ask, just to see what people are thinking. But when we test, we ask questions like, “Who was talking here?” “Why did he beat his chest?” “What does sɛmbu mean?” “Who did Moses see at the top of the mountain?” If they say, “Moses saw Jesus at the top of the mountain” we probably did something wrong in translation. They have not understood the correct meaning. Therefore the translation is likely inaccurate, which we only know by asking the intended audience what they understood.

I thought this would be my last translation post for now, but I am seeing that it might be helpful to cover the other aspects of a good translation: clarity, naturalness, and acceptability. Look for more posts to come!

4 thoughts on “On Accuracy”